‘In our cynical society, it is often the case that mining companies build up their profits while not reporting to their shareholders the environmental and social costs that are absorbed by the surrounding poor and disempowered communities.” In Johannesburg, Mariette Liefferink was brimming over with this inflamed thought as she composed a letter to the US-based bank JPMorgan to express her outrage at the company’s misdeeds.

“Our regulators are often compromised and give in to the pressure of the coal mining industry. [They] do not have the political will to enforce our laws,” Liefferink said.

Liefferink, who is president of the South African NGO Federation for a Sustainable Environment, addressed her letter to Chuka Umunna, the global head of sustainable solutions at the world’s largest asset manager.

After a political career that included a run for Labour leader, Umunna turned his hand to investment banking. “It’s the other side of the fence of actually trying to change the world,” he said a few months after joining JPMorgan. “I don’t want it to sound too grand but that’s what this bank is in the business of doing.”

Umunna now leads a team that helps JPMorgan, one of the world’s biggest banks, raise money from investors who care about sustainability. He works for JPMorgan’s investment bank rather than the asset management arm that runs these funds. In that role, Umunna says, he oversees “JPMorgan Chase’s sustainability strategy across EMEA and the franchise’s own efforts to integrate sustainability into its own operations and business activities in the region”. He did not respond to Liefferink’s email.

“Most of the people, when they do drink this water they get stomach aches,” she said.

Despite a backlash against so-called “woke capitalism” over the past few years, this remains big business. Investing that accounts for environmental and social issues – known as ESG – is expected to surpass $40-trillion by 2030. And it’s vital in order to limit global heating to 1.5°C and avoid catastrophic climate change, according to the UN.

Bottom of infographic: Returns in dividends plus capital gains between Q4 2021 and Q2 2024. Given the difficulty of knowing the buy and sell prices of the shares, intervals have been constructed to measure the returns. The minimum is the lower limit and the maximum is the upper limit.

Yet some of the investment funds JPMorgan calls “sustainable” are going to the mining giant Glencore, whose coal activity in South Africa is causing devastating environmental damage. In fact, supposedly sustainable funds run by JPMorgan Asset Management are supporting Glencore to the tune of a quarter of a billion dollars, the Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ), Voxeurop and the Daily Maverick can reveal.

Chronic pollution

In the heart of South Africa’s coal belt, longtime residents of the mining town of Phola, Mpumalanaga, say they don’t trust the local water supply. “When you open the tap – if by the grace of God water comes out that day – it’s rusty, it’s smelly, it’s not something you can consume,” said a mother who asked to remain anonymous for fear of speaking out against the powerful mining companies.

Diep River cleaning complaint by a resident on 26 January 2024 by Kristin Engel on Scribd

“It becomes frustrating because if you can’t drink the water, you [have to] buy water. If you bathe in it, you get skin rashes.” Her son, now 16, started developing regular skin rashes when he was six. “That was when I started noticing it’s not an allergy but there was something wrong with the water.”

Daisy Tshabangu (52) moved to Phola because her family worked at the coal-fired power station that looms on the horizon. “Most of the people, when they do drink this water they get stomach aches,” she said.

Glencore runs three mining complexes in the area. According to a recent government report, obtained via a freedom of information request, one of those has been breaking environmental laws since 2017. The company’s Tweefontein coal mine has been accused of several breaches including seriously contaminating a local river, storing hazardous waste in open containers and failing to fix broken walls at a sewerage facility.

Glencore says its water treatment plant supplies clean water to Phola as part of its “commitment to sustainable development”. But residents say this isn’t happening. “Their failure to treat the water comes back to the community and ends up getting the community members sick, people that rely on that water,” said Collen Mabelane from Mining Affected Communities United in Action.

Despite repeated requests to clean up its operations, the Tweefontein mine was still in breach of a number of environmental laws as recently as November 2023. But the company’s licence has not been revoked.

Phola residents feel abandoned by the companies whose mines dominate the landscape. Unemployment is high, infrastructure is crumbling, and basic services are not being met. “We don’t benefit from the mines,” Tshabangu said. “There’s a lot we don’t have but we are surrounded by mines. So, to us, it seems like we are being sidelined as a community.”

A few months ago, researchers from the University of the Witwatersrand went to Phola to test the water. Daily Maverick was told by anonymous sources that the tests showed nothing alarming. It is worth noting that the university has ties with Glencore, which has sponsored its graduate students and hosted some of them at Tweefontein Mine.

Matthews Hlabane, founding member of the South African Green Revolutionary Council, has also recently performed tests with his fellow activists. The results showed contamination and acid mine drainage.

/file/attachments/2864/2025-10-02_11-40-19_323752_1_130054_764956_d04245f504cce7d5b7c7ba6db66012ec_988590_fe4f03f5268617ccda9b4502c8588600_1_573714_1_454616.jpg)

Glencore told TBIJ that mitigating negative impacts of its mines is imperative to building trust with local communities, which it maintains through ethical and responsible business practices.

The company said it is not directly responsible for water supply to Phola, which is a municipal service, but contributes to a reservoir that also receives water from other sources. It said it monitors the quality of the water provided by its treatment plant weekly to ensure it is suitable for consumption. The company said it has been taking action in response to Department of Water and Sanitation inspections since 2017, and that incidents identified in the 2023 audit have been addressed.

Paying the cost of coal

South Africa is a country hooked on the world’s most polluting fossil fuel. The vast majority of its energy is generated by burning coal, and most of that is mined in Mpumalanga. But the industry has devastated local communities and contributed to a chronic water crisis affecting more than four million people, according to campaign groups.

The Mpumalanga mines form a small part of Glencore’s global operations. It is the world’s fifth-biggest coal miner, selling more than 100 million tonnes in 2023 – including from the notorious Cerrejón mine in Colombia where a litany of human rights abuses and environmental destruction have taken place. In short, Glencore is not the kind of company investors might expect to support when putting their savings into a sustainable fund.

JPMorgan Asset Management, however, had more than $260-million invested in Glencore shares and bonds via supposedly sustainable funds in the second quarter of last year, according to data from LSEG and fund reports.

JPMorgan’s green funds investing in Glencore

Bottom of infographic: Evolution of funds investing under EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation’s Article 8 (promoting social and/or environmental characteristics), in US dollars.

Furious that so-called sustainable finance is supporting Glencore, Liefferink wrote to Umunna in November 2024 about the environmental risk, ecological degradation and pollution associated with JPMorgan’s investment in the company. She highlighted two JPMorgan funds with ESG in their name, both of which had millions of dollars invested in Glencore.

Liefferink urged the bank to review its investments in Glencore due to the company’s alleged breaking of environmental laws, as well as the pollution, wildlife damage and environmental risk its activities were causing. Umunna did not respond.

A wider problem

After a rapid rise in popularity, ESG investing is the subject of increasing scrutiny around the world. Regulators are trying to settle on what it means and create labels that are easy for investors to understand.

TBIJ and Voxeurop analysed a number of funds JPMorgan lists on its “sustainable investing” page that promote “environmental and/or social characteristics”. JPMorgan explains that this may include “effective management of toxic emissions and waste, as well as good environmental record”. Crucially, the funds have certain restrictions on investments in companies involved in thermal coal. On the face of it, this would appear to prohibit those funds from investing in Glencore.

The devil, however, is in the detail. JPMorgan specifies that at least 51% of investments held by its sustainable funds must have positive environmental and/or social characteristics. The remaining 49% can be invested without such restrictions.

Jakob Thomä, chief executive of Theia Finance Labs, a climate think tank, said: “The overwhelming majority of retail investors, in my view, would feel misled if they knew that was the criteria for labelling something as a sustainable fund.”

He said that some sustainable funds may therefore be breaking EU law, which brands anything that “deceives or is likely to deceive the average consumer” as misleading commercial practice.

JPMorgan’s sustainable funds also exclude companies that make more than 20% of revenues from thermal coal extraction. Despite being one of the world’s biggest coal companies, Glencore slips under this threshold in terms of revenues but in terms of actual profit coal mining accounts for nearly half.

JPMorgan declined to comment on the findings of this investigation or to answer whether it considered Glencore an investment with positive environmental and/or social characteristics.

In an interview with Umunna in 2024, it was suggested to him that the finance sector is moving towards “sustainability 2.0” as regulators increase their scrutiny of ESG commitments. “I think the first version was one where people essentially were marking their own homework, setting their own targets and rules and there wasn’t so much regulation,” Umunna said.

He said those issues won’t go away with new rules but the burden will instead be placed on the ultimate investor. “The effect of the regulation is to promote and put more disclosure out there which enables investors to make better-informed decisions about what they do.” DM

EU-regulated green funds* named using terms mentioning public good investing in Glencore

Bottom of infographic: Investments value in US dollars in 4th quarter of 2023. (latest available full update from the LSEG database). DM

This article is part of the investigation coordinated by Voxeurop with the support of the Bertha Challenge fellowship. Stefano Valentino is a Bertha Challenge Fellow 2024.

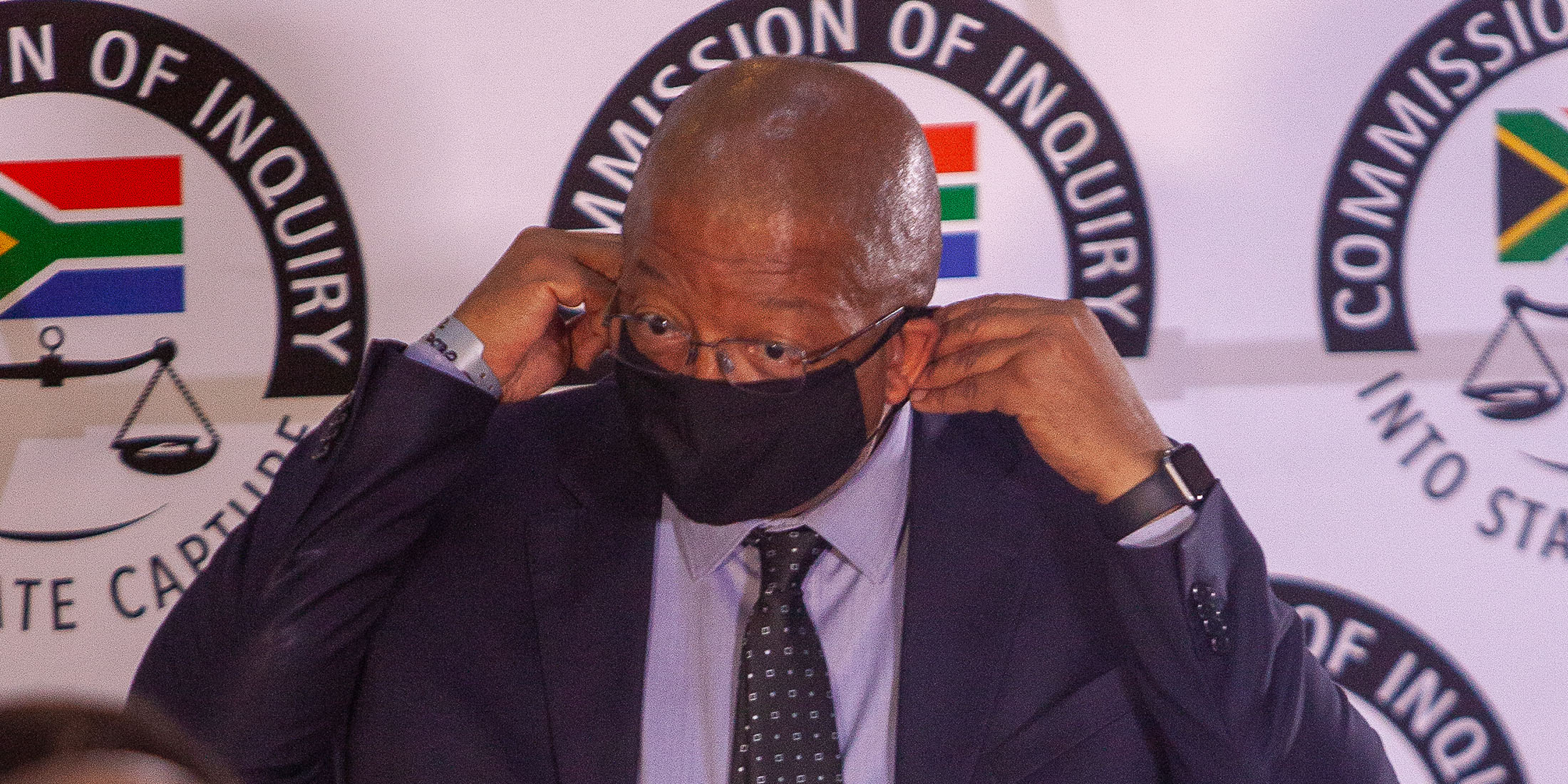

Free State head of the Department of Human Settlements Nthimotse Mokhesi testifies at the Zondo Commission in Johannesburg on 21 September. (Photo: Gallo Images / Papi Morake)[/caption]

Free State head of the Department of Human Settlements Nthimotse Mokhesi testifies at the Zondo Commission in Johannesburg on 21 September. (Photo: Gallo Images / Papi Morake)[/caption]