A high court judge recently highlighted the issue of racial representation in the legal fraternity when he questioned why there were no black lawyers involved in a case about black economic empowerment (BEE), and legal practitioners are now expressing concern that racially skewed briefing patterns could affect the quality of the judiciary in future.

Briefing patterns refer to the way in which advocates are hired to participate in a case, either by private attorneys or by the state attorney on behalf of the government. Advocates do not engage directly with clients, but rely on attorneys to refer work to them.

The Pan African Bar Association of South Africa (Pabasa) and the Black Lawyers Association (BLA) believe the issue poses a real risk to the functioning of the Bench, which is the third arm of government.

The issue of skewed briefing patterns garnered public attention after high court Judge Mandlenkosi Motha called on advocates in a case involving Peri Formwork Scaffolding and the head of the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Commission to make a 10-minute submission about why no black lawyers were involved in the case. Motha questioned whether this amounted to a violation of Section 9 of the Constitution, which deals with the right to equality.

Advocate Johan Brand called Motha’s request “totally inappropriate” and opted not to respond to it, as requested. Some in the legal community have applauded Motha’s approach, and the BLA said the case is indicative of a broader problem of skewed briefing patterns.

Pabasa agrees that the issue goes beyond a single case. Instead, it points to a larger problem in the legal community – that black and female lawyers are not brought into complex cases.

Vuyani Ngalwana SC, who has been designated to speak on transformation issues on behalf of Pabasa, says that, if not resolved, the issue of unequal briefs could negatively affect the functioning of the judiciary.

“What I have suggested is that we should have a conference or a symposium, because it seems to me we’re talking past each other. Either people don’t understand what these skewed briefing patterns are, or they are in denial [about] whether it is indeed happening,” Ngalwana said.

“I’m saying, let’s talk about whether it does exist or not. And I’m sure the evidence is going to come out that it does exist.

“Then let’s talk about how we can address these issues. What are the risks to the South African legal system, because it is broader than just briefing patterns? This thing creeps up all the way to the standard of the judiciary and the standards of the judgments that we get.”

Ngalwana says an industry-wide symposium is needed to address the concern that white lawyers are getting the bulk of work in particular areas of law. He adds that Pabasa’s national executive committee “has now formally taken the decision to approach the Legal Practice Council to arrange the industry-wide symposium”.

Context

BLA president Nkosana Francois Mvundlela expresses a similar concern about the broader impact of the issue.

“When talking about… briefing patterns, it is important to understand the context. And the context is that a strong legal profession will produce a strong judiciary. The issue of briefing patterns goes beyond the issue of incomes of lawyers,” he said.

When judges are chosen to sit on the high court Bench, they are often chosen from the ranks of senior advocates or magistrates. During interviews, they need to demonstrate wide-ranging experience, as the high court often deals with complex commercial cases, competition law, insolvency and administrative law.

Often, black advocates and women do not have sufficient experience in these areas of law, but have more experience with criminal and family law.

Judges Matter researcher Mbekezeli Benjamin, who has seen this issue play out in interviews for potential judges many times, says skewed briefing patterns pose a risk to the effective functioning of the judiciary.

“This is something that we often see in Judicial Service Commission interviews. Part of what you must show is that you have broad experiences. You must have grappled with cases of differing complexity.

“This is because, as a judge, you will be required to deal with a whole gamut of cases. One week there is criminal law, the next week family law, the next week there might be an administrative law case.”

Benjamin notes that many complex cases are handled by the same few large law firms and their lawyers tend to brief the same advocates.

“The argument has always been that they have to brief someone that they trust. But often those assessments are very subjective. Sometimes those people don’t do… well, but continue to be given work. That kind of benefit of the doubt is not given to black lawyers, women and younger advocates,” he said.

He adds that some areas, such as competition law, are “effectively a closed shop” where the same lawyers are seen over and over again.

“The Constitution requires that the judiciary looks at gender and race in its composition. That means that it must broadly represent the country.

“If we aspire to a transformed judiciary but don’t have a pipeline of practitioners who have the proper experience, it is a risk. It is a serious risk to the entire legal enterprise. If we have a weak judiciary, we will have a weak rule of law.”

Benjamin says a symposium would be a useful intervention, but it would need to be supported by proper data to show which speciality areas have the biggest problems.

Government briefs

Legal practitioners are also concerned about the role of the government in dealing with skewed briefing patterns. The Office of the Solicitor-General released statistics on how it had tackled briefs between 2019 and 2024.

The statistics indicated that, in 2019, it had an internal target to provide 83% of its briefs to previously disadvantaged individuals and reached an actual outcome of 93%. By 2024, 95% of briefs went to previously disadvantaged people.

In 2019, it aimed to brief women in 39% of cases and attained that target. By 2024, it reached 42% in briefs going to women.

However, Mvundlela says there is a need to examine these numbers further to ensure that the same people are not being briefed repeatedly.

“It is also about age, gender and a skills transfer. We are saying that the Solicitor-General’s Office must be able to go all out. Even when there are two black people, the other must be a young person who will be able to learn,” he said.

Read more in Daily Maverick: All-white, all-male legal teams are wrong on so many levels

Mvundlela says the BLA is concerned that the amended Legal Sector Code of Good Practice on Broad-Based BEE has not been published by the Department of Trade, Industry and Competition after being published for comment in July 2022.

The code, which was developed by the Legal Practice Council in conjunction with the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development, “aims to address inequities resulting from the systematic exclusion of black people from meaningful participation in the economy to access South Africa’s productive resources, economic development, employment creation and poverty eradication”.

Mvundlela says the publication of the final code will provide much-needed guidance to the legal profession on how to ensure more representation. DM

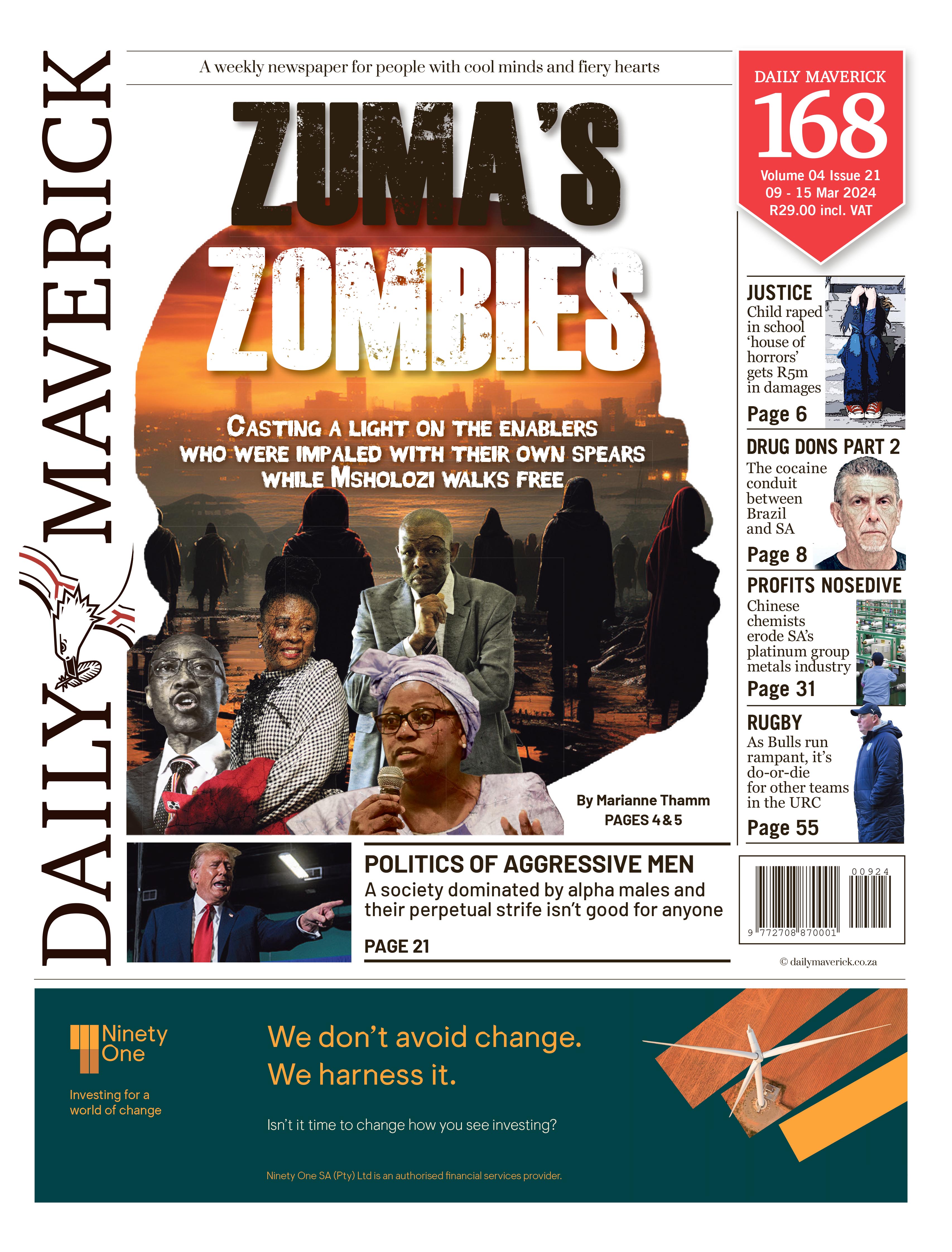

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper, which is available countrywide for R29.