We are about to move into the period of the year associated, at least theoretically, with good cheer. One of the questions I get asked the most as a journalist is why the press never seems able to join that movement.

And this year, in particular, the criticism that the press has only bad news to report is particularly telling. Internationally, there are not one but two heartbreaking, almost unbearable military conflicts, and the COP28 climate change talks, which began with an assessment by entrepreneur-turned-global health interventionist Bill Gates announcing that the world is probably not going to meet its temperature-rise targets. COP28 is being held in a petro-state, so what could possibly go wrong?

Locally, I meet more and more people who tell me they don’t bother to read the news any more because it’s too depressing. The protagonists of the old State Capture outfit seem to have got away with it and the protagonists of the new State Capture outfits seem to be relentlessly pushing forward. Eskom’s travails seem to be getting worse, and other state-owned enterprises seem to be joining Eskom’s ranks. And so on, and so on.

When people ask me why the press is so negative, I guess they feel their missions, as humans, whatever those might be, are threatened by an atmosphere of gloom. Pessimism tends to reduce effort and encourage a sense of hopelessness. And, of course, they are right: the performance of our economy is partly a function of confidence that it will perform well.

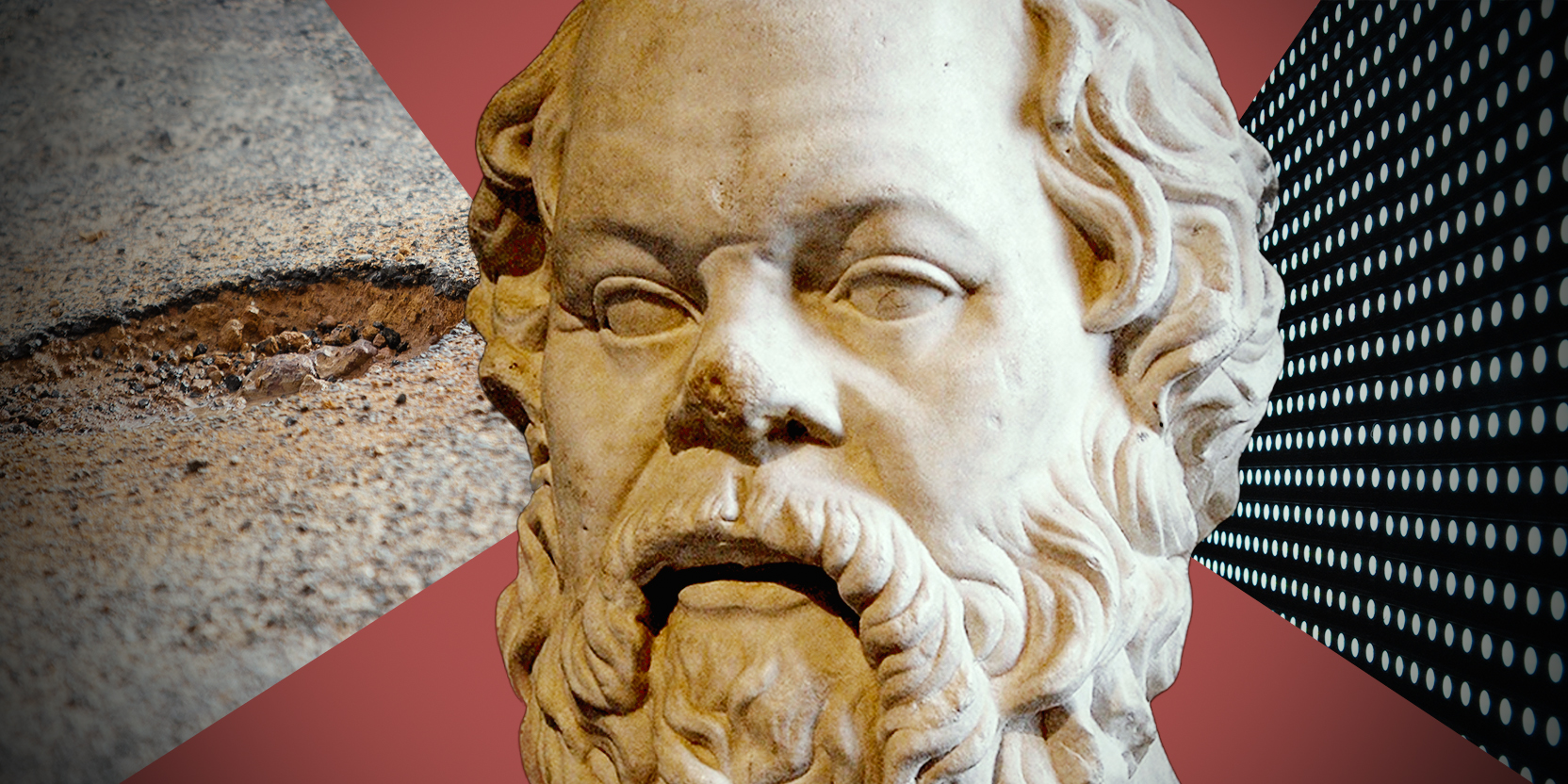

We would all be better off, they argue, if we just turned off the news and focused on the things we can do. In other words, their argument is a challenge to Socrates’ old injunction that the unexamined life is not worth living.

Well, because you can these days, I went off and asked Socrates what he was on about. A website called character.ai allows you to summon the avatars of a variety of well-known people, including Socrates, and have a conversation with them.

I asked “Socrates” — an AI model built from all of his known works and teachings — why the unexamined life was not worth living. This was “his” reply:

“Because our beliefs make up the fabric of our lives. If we do not examine them, we are left with an untried and untested worldview that could potentially hinder our actions and decisions every step of the way. It would be like building a house without a foundation, without taking into consideration the environment, the climate, the landscape, and the construction materials to suit it. The house you end up building will either be ineffective or downright unsafe. In the same way, if you do not examine the beliefs that you base your entire life around, you open yourself up to the possibility of making poor choices and having a life not worth living.”

“Yes”, I retorted — slightly getting into the groove of the Socratic method here — “but surely some people would be overwhelmed by the problems they face, so it might be better for them to live in partial ignorance?”

“Ah, but I’m afraid that is where the common mistake lies. When people refuse to examine their beliefs, they are not simply living in ignorance, rather they are living in denial. Ignorance is a consequence of lack of knowledge. Denial is an intentional refusal to acknowledge the truth of a situation. So living in partial denial is never a better choice than living with an examined life.”

You have to say, this is pretty impressive, both on the part of Socrates and the LLM. I asked a few more questions, and then, being the know-it-all teacher that he is, he started asking questions back. There are things, I said, I would prefer not to know about. He asked for an example. False comments on X (formerly Twitter), I said. “Ah,” he said, in a slightly irritating knowing sort of way, “that’s understandable.”

“Do you think it’s possible to reduce the number of false comments on X?” he asked. And so we went on. Eventually, I got bored of answering my own questions, but the point was well made: truth is not a choice.

In fact, I would argue that by being negative, the press is, in its own perverse way, being positive. How can that be? Simply because problems don’t get solved unless they first get aired. Reaction is tied up in the realisation that there is a problem to be solved.

And this, by the way, is why people tend to not read positive stories. In the media now it is possible to see with indelible precision how much of your audience reads which article. And trust me, fluffy, feel-good stories get read by very few people. That makes absolute sense: if you are driving on a road, what you want to know is not whether there is a road, but whether there are dangers on the road.

If action is predicated on the realisation of, for example, that there are potholes in the road, why are the political authorities not fixing our potholes, both literal and figurative? Now there is a question for you. Perhaps we should ask Socrates. Or Einstein.

Or, perhaps, the political figures themselves. Bless. DM

Business Maverick

After the Bell: Why are our potholes not being fixed? Well, let’s ask Socrates