I wasn’t the biggest reader in the family; my father and sister just ate books whole. They thundered through them at a gallop I could never hope to match. I remember being slightly aghast when I visited friends’ families who actually talked to one another during supper. I wondered later whether our reading-over-supper tradition was a good thing. Surely, families should, you know, encourage human contact and interaction and that stuff? I don’t know – perhaps.

I remember as a kid, watching one of my sister’s would-be boyfriends sidle over to my father before a date. My father was in the normal pose: bare-chested, in rugby shorts, hunched over a book, bathed in lamp-light.

Desperate to impress him, my sister’s “gentleman caller”, as her string of boyfriend hopefuls came to be known, asked my father what he thought of Wilbur Smith. Wow. Big mistake. My father barely looked up (and when he did, it was to stare witheringly over his reading glasses) from his beloved James Joyce.

“Thin shit,” he said, dismissing the unfortunate guy with a determined stare at his pages.

With this history, reading the results of the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (Pirls), released this week, was personally painful. The study aims at benchmarking literacy around the world, allowing me to ask where you think SA came in this international comparison. Would you believe, absolutely stone last?

Now, there are a couple of caveats here: not all countries around the world take part. Most of the countries that participate are high- or middle-income countries. So, it would not be true to say that SA has achieved “worst-in-the-world status”, as tempting as it might seem. In total, 57 countries take part, and there are some regional breakdowns within a country too.

SA’s dismal results come with a caveat because a large number of scores were so low there were doubts about their reliability. If those are excluded, SA shifts up a few places.

The ranking includes both scores, but there was clearly an argument here between SA and the Pirls organisers to try to make SA’s pitiful score look a bit better.

But just to give you a taste of the extent of SA’s underperformance: the absolute best South African score – the number one top score, would fall in the bottom third of the world’s highest-scoring country, Singapore.

Not only is SA’s score the lowest, but it’s also the lowest by a shocking margin. SA’s unadulterated score on the test was 288 – Singapore’s was 587.

It gets worse.

The difference between the highest and lowest scores within a country was substantially wider than in any other country. SA’s performance compared with its peers was also abysmal: Egypt’s kids got 378; Brazil’s kids got 419. What this means is that around 81% of SA’s Grade 4s can’t read for meaning. It’s. Just. Gobsmacking.

But we do need to cut ourselves a bit of slack here. Almost all the countries in the study would have most likely come from cultures where the language of the test and the kids’ home language would probably have been the same. That’s not true of SA, and it makes a big difference. And the test measures pretty young kids – Grade 4s – who are normally 10 years old.

But even if you grant us these points, there is another measure to worry about.

Since the previous test was done in 2016, SA’s score has declined, and not just by a little bit (in 2016, SA’s score was 320). It’s true, the test was done during Covid and teaching was hard, locally and internationally. The international average was slightly down. But a lot of countries improved – and nobody declined as much as SA.

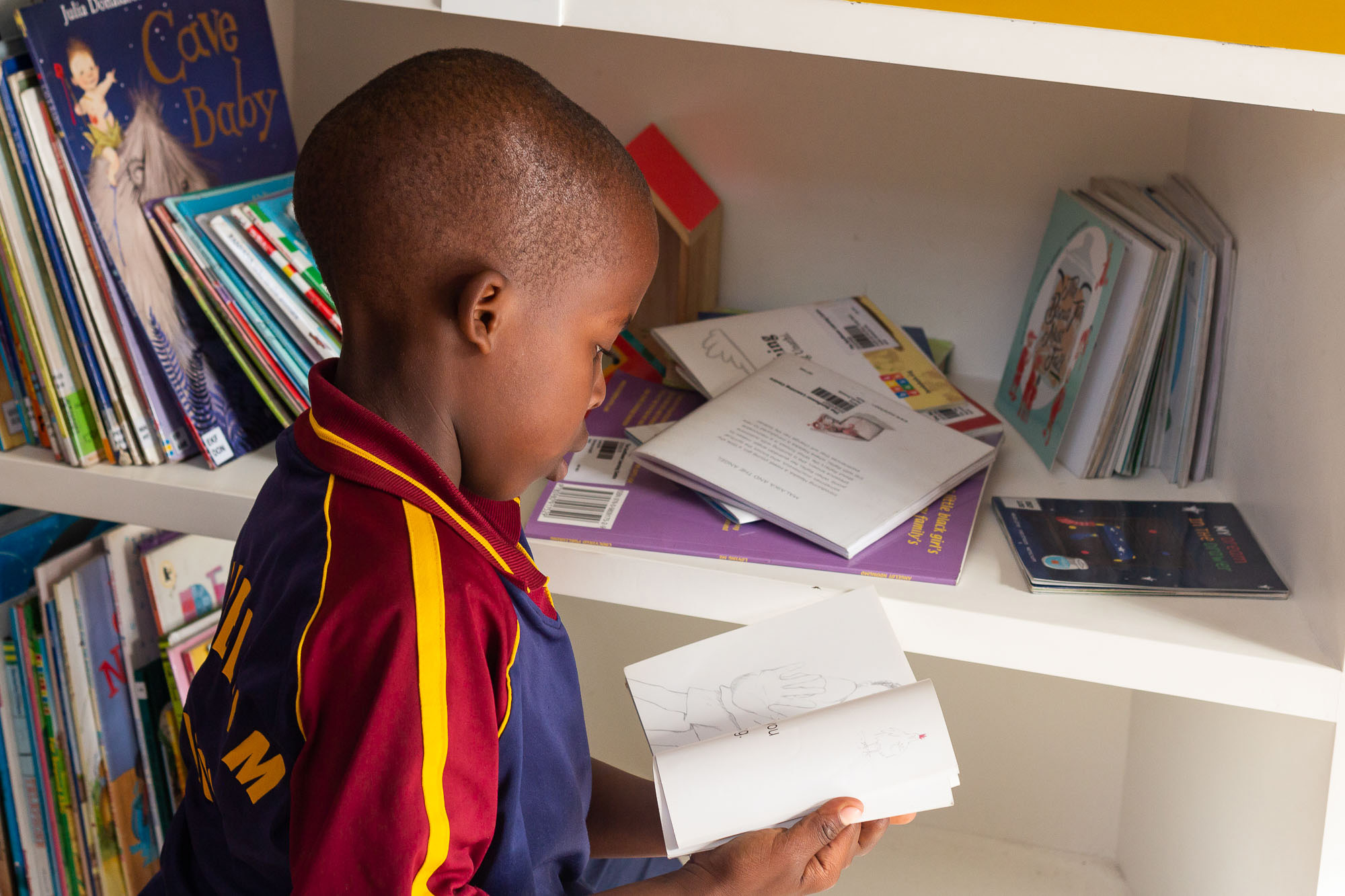

So, there are many people to blame for this, but there is one group you can’t blame – the kids themselves. Why? Because one of the questions they ask before the test is whether they like reading.

This is going to astound you. SA’s kids are way, way above the international average. Twice as many of SA’s kids answered, “very much” to that question compared with, for example, American kids. On that score, SA beats, among others, Germany, Russia, France and a host of others.

But you know, that just makes me even more depressed. Other improvements in SA’s education have to be taken into account: stable curriculums, national distribution of workbooks, and the National School Nutrition Programme are all working, mostly. So, you can’t blame that.

So, then, what is it? If the reason for SA’s poor results is not the enthusiasm of the learners, then, I suspect, there are two main reasons left. Poor teaching and, sadly, poor parenting, because when all is said and done, the family is where the real learning takes place.

As I say, I was blessed to be born into a family with no manners. DM

Business Maverick

The kids are alright - why SA’s poor reading literacy results can’t be blamed on learners